Micronesian reflections on the state of Pacific regionalism

By Katerina Teaiwa, Vincente M. Diaz and Julian Aguon posted on March 6, 2021 by the newoutrigger.com

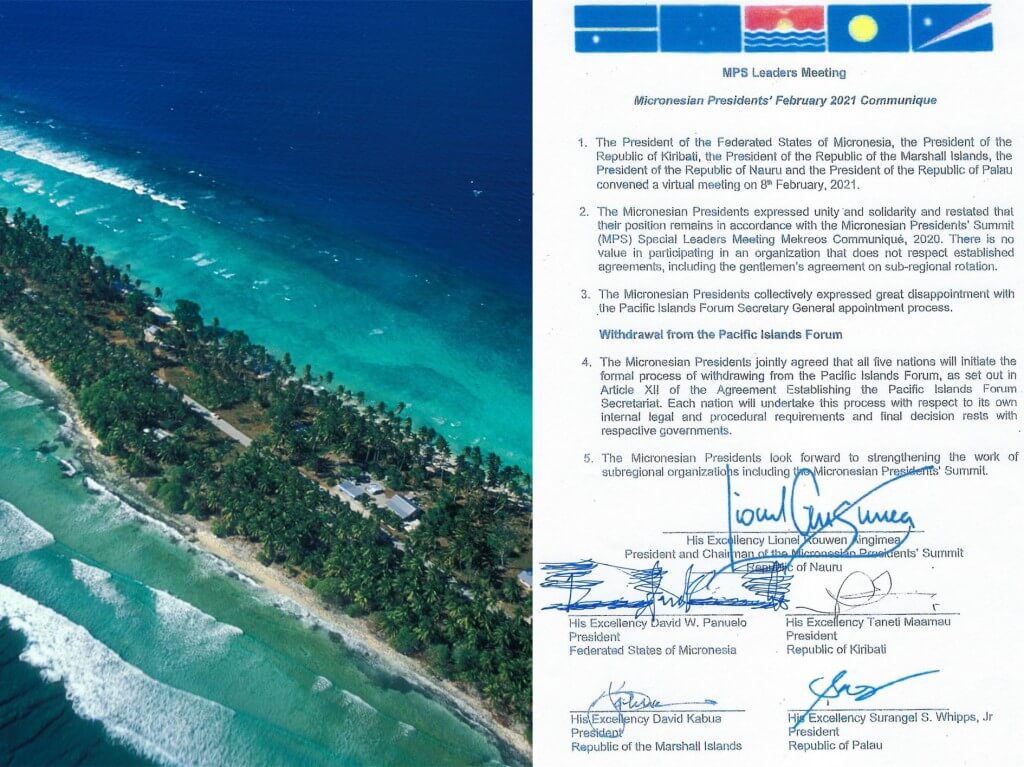

Marshall Islands and Micronesian Presidents’ February 2021 Communique. Image courtesy of Getty Images.

It has been a tumultuous time for Pacific regionalism. After the election of a new Secretary General, former Cook Islands Prime Minister Henry Puna, five countries from the central and northern Pacific, almost a third of the states that make up the region’s peak political body, the Pacific Islands Forum, agreed to leave because they believe the underlying values and principles of kinship and trust that have underpinned the Forum for fifty years no longer hold. The former President of the Marshall Islands, Dr. Hilda Heine tweeted: “Congratulations to the newly elected PIF SG, the Hon. Henry Puna. In not honoring the well known gentlemen’s agreement, however, the process left a bad taste in our mouths, and the realization that Micronesian countries could never be integral or significant players in the PIF.”

The hot takes on the impact of the Micronesian walkout came in fast and furious from journalists, political commentators, civil society and Australian think tanks.

The extraordinary view offered by the Lowy Institute’s managing editor, Daniel Flitton, that described the Micronesian Presidents decision as a “toddler’s tantrum” was a sharp reminder of the patronising and condescending views still harboured towards Pacific Islanders from seemingly polite and measured foreign affairs corners. Flitton’s piece was viewed as neo-colonial and racist by many and in an Australia still reeling from the fallout of a report on rampant racism in the ranks of that country’s beloved Australian Football League, Lowy swiftly jumped into damage control.

Director Jonathan Pryke said he was devastated to see how the article impacted the region and: “the best Pacific content comes from Pacific voices.” No doubt he was genuinely sorry, but if the best content on the region comes from Pacific voices then why is Pacific expertise and commentary across all sectors in Australia, particularly academia, foreign affairs, media, and policy, dominated by everyone but actual Pacific Islanders? Australian institutions have trained countless Pacific students, postgraduates and PhDs and hired very few of them, or elevated them to thought leader status.

There have been very few Micronesian voices commenting on regional politics in mainstream media beyond the words of a few political leaders. Most recently, Palauan President Surangel Whipps Jr. Whipps made the views of the Micronesian leaders and the nations they represent, outlined in the Mekreos Communiqué, very clear. Micronesia “saw no value in participating in the forum, should it fail to honour the existing agreement on subregional rotation.”

As Micronesian scholars with a combined and broad background in contemporary and historical Pacific cultural and political dynamics, gender, international law and critical analysis, we thought it would be helpful to unpack some of the issues including the heavily referenced “Pacific Way” and the impact of subregional identities and solidarities. We also spoke with the former culture advisor to the human development programme of the Pacific Community, Elise Huffer, to shape our thinking, we believe two of the most underappreciated elements of Pacific regionalism are history and culture.

Pacific Island Forum members met in Funafuti, Tuvalu in 2019. Image courtesy of ABC News/Melissa Clarke.

Firstly, there appears to be a strong showing of solidarity between the Micronesian leaders – what has led to this? The Melanesian Spearhead Group and to an extent, the Polynesian Leaders Forum, had far more visibility compared with formal Micronesian groupings until now. There are clear differences between Palau, the Marshall Islands and the Federated States of Micronesia with their close association with the United States through their Compacts of Free Association, compared with Nauru and Kiribati who have historical ties with Australia and the United Kingdom, particularly after World War I. However, they all share very similar experiences of Japanese occupation during World War II, and either outright nuclear testing in the case of the Marshalls and Kiribati, or fighting for anti-nuclear laws in the case of Palau. Furthermore, Micronesia is far more than a grouping of post-colonial states, their connections are built on historical exchanges, networks, and knowledge systems that reach back thousands of years.

The strong showing of Micronesian unity should not be underestimated. Unlike the two other subregions, with some exception in the case of the Melanesian countries, the island nations north of the equator actually suffered together the direct atrocities of World War II. Those that were under German, Japanese, and American colonial rule also shared a post WWII history under the American and UN sponsored strategic trust territory experience that included a hard look and weighing of the pros and cons of political unity against each’s unique cultural and political histories.

The political leaders of this region know very well the stakes of that historical calculus and don’t take it lightly. Likewise, the shared experience through nation rebuilding under the Cold War and since America’s strategic pivot post 9-11 amidst China’s economic, political, and military machinations—and Australia and New Zealand strategists know this well—forges in our leaders a direct and visceral experience of Micronesia’s vulnerabilities, again shaped by a collective experience of World War II and the conflicts and implications for colonial rule that preceded it.

The Micronesian bloc’s willingness to stand together is inspiring for how it differentiates the geopolitical and environmental realities and the political and cultural diversities within the subregion from the abstract idealism of pan-Pacific regional unity, again, in the face of grave challenges, whether military, economic, or environmental.

Secondly, their expression of political unity is forged on common political, historical and contemporary grounds as well as on remarkable diversity within the colonial construct called “Micronesia.” That their decision is cultural affront ought not be misconstrued, nor condescended to as infantile sentiments that reflect a collective inability to discern what’s grave and what’s not, what has merit and what doesn’t. Micronesian leaders did not come to their decisions merely over what Flitton described as “a job application.” Against a wider geopolitical backdrop of a rapidly spreading canopy of U.S. militarization, ongoing Chinese aggression in the South China Sea, and North Korea’s nuclear threats, the editorial choice to reduce the concerns of a third of the Pacific to nothing more than a “tantrum” is tone-deaf in the extreme. In real ways, lives are on the line so it would be nice if the peanut galleries of the colonial/settler powers could quiet down some so that we who are on the frontlines can hear ourselves think.

We write this as scholars, artists and practitioners who believe in pan-Pacific unity and whose scholarship comes from a learned commitment to it, but also as Micronesians who know how it feels to be consistently erased by the decisions, actions, and imagination of others, including other Pacific Islanders, who fail to grasp that their views of the Pacific simply don’t stand for the entire Pacific.

Micronesian countries have punched well above their weight in recent years—on everything from ocean policy to nuclear weapons to climate change. That the Micronesian bloc’s candidate for the Secretary General slot was Marshallese is an especially hard pill to swallow, as the Marshall Islands has proven again and again, and perhaps more spectacularly than any country on earth, that smallness is a state of mind. From securing global consensus in the lead-up to the Paris Agreement to suing the Nuclear Nine in the International Court of Justice to stewarding the Climate Vulnerable Forum, the Marshall Islands has given us so many reasons to be proud. That none of that may have been enough to translate into regional standing is unthinkable.

However, thirdly, as much as we may agree with these leaders, the cloaking of their complaint in terms of the violation of a “gentleman’s agreement” most certainly calls attention to a system that is still fundamentally patriarchal, that favours men as “fathers” of island nations gendered as “mother countries” over women leaders, even in matrilineal island societies such as the Marshall Islands, the Federated States of Micronesia, and Palau. There are Indigenous forms of inequality along gendered, classed, and sexual lines that predate Euro-American and Asian imperialisms and have their own distinct forms of interlocking oppressions along culture, class, race, religion, gender and sexuality lines. For whatever good reasons we have to take sides in regional conflicts, we also cannot afford to think that any of us are innocent. We need more home-grown Indigenous Feminist and/or Indigenous women’s critiques of colonial and Indigenous patriarchy and heteronormative politics as modelled in the critical work by women of our region, like the late Teresia Kieuea Teaiwa, Katerina Teaiwa, Christine Taitano DeLisle, Laura Souder, Angela Robinson, Kathy Jetnil Kijiner, and MyJolynn Kim, to name a few.

For as much as our work on the global stage is necessarily focused outward, such as insisting that the biggest emitters of greenhouse gas emissions are held accountable for their outsized share of anthropogenic climate change, we have to be morally strenuous at home too. We have to take a harder look not only at how others have failed us, but how we have failed each other. As a region, we still have work to do. We could start simply by remembering that regionalism is first and foremost about solidarity and that solidarity is a verb.